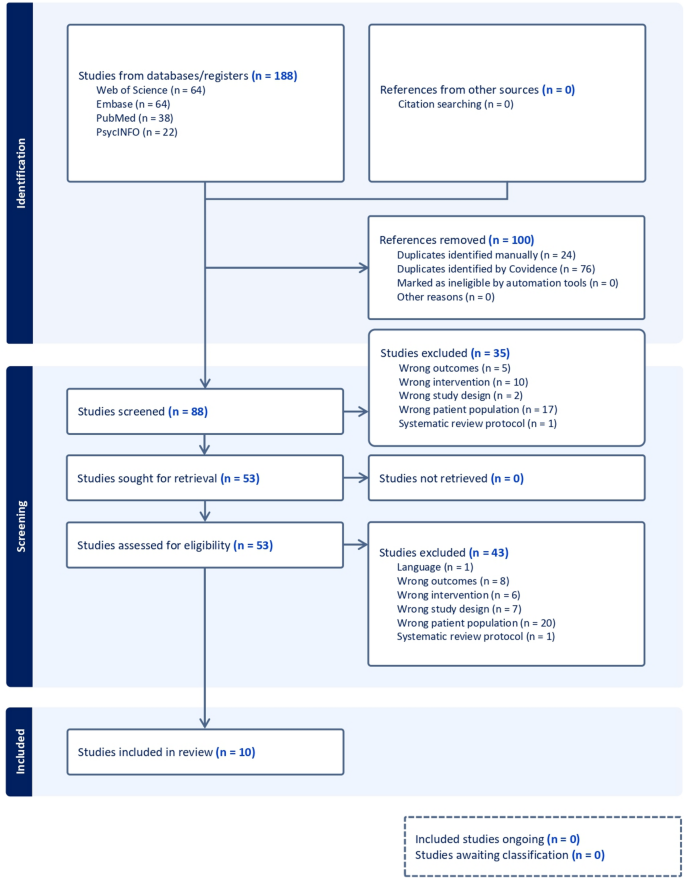

A systematic search initially identified 188 studies. Ten systematic reviews and meta-analyses met eligibility criteria for data extraction. The entire process, from database search to final inclusion of systematic reviews is described in Fig. 1. Details of the studies excluded during the full-text eligibility phase are provided in the supplementary file S2.

Characteristics of the systematic reviews

The characteristics of the included systematic reviews are summarized in the supplementary file S3.

The systematic reviews were published between 2018 and 2023, with four published in 2021 [33,34,35,36]. Most of them were conducted in China [8, 36,37,38,39,40], several involved collaborations: Hong Kong, USA and China [37]; Colombia and Spain [41], and Singapore and Norway [34], one was in Singapore[35], and another in Canada [33].

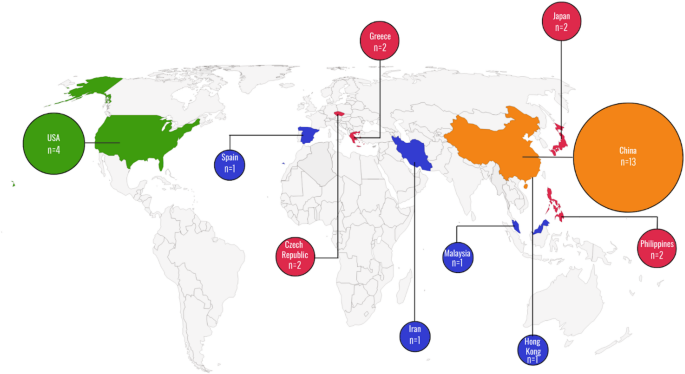

The distribution of individual studies (N = 29 for the 10 systematic reviews), can be seen in Fig. 2. Most of them (13) were in China and the geographic distribution is notable concentrated in the Global North.

Geographic distribution of included individual studies in systematic reviews and meta-analyses. Geographic distribution of N=29 individual studies reported in the 10 systematic reviews which matched the inclusion criteria in the umbrella review ((P: MCI/Dementia; I: Dance; O: Cognition) represent a paucity of studies from the global south

Participants’ characteristics and interventions

The characteristics of the participants and interventions of the included systematic reviews are summarized in the supplementary file S4.

The total sample comprised 6,343 participants, with an average age ranging from over 60 to 85 years. Most participants were women.

The reviewed systematic reviews encompassed a diverse range of dance genres, including ballroom (all studies), salsa and tango [34, 37, 40], square dance [8, 34, 36, 37, 39, 41], modern dance [37], aerobic dance [8, 33, 36, 37, 39, 41], folk dance [34, 36,37,38], and dance therapy [37]. Details of the Dance Intervention Diversity and Distribution in the included systematic reviews and meta-analyses are provided in the supplementary file S5.

All the systematic reviews demonstrated the potential of dance on cognitive domains. However, some results are heterogeneous [41], indicating the presence of significant and non-significant findings.

The interventions ranged from 6 weeks to one year with a frequency of 1 to 7 times a week and ranging from 20 to 120 min. All systematic reviews showed results comparing dance intervention with a control group [8, 33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41], and 7 with active control groups [8, 34, 36, 38,39,40,41].

Outcomes and instruments

A broad range of cognitive domains were assessed, including cognitive function, memory, attention, and executive function. Various instruments were utilized, including global cognitive measures, such as the MMSE, MoCA, and Alzheimer’s Disease Assessment Scale-Cognitive Subscale (ADAS-Cog). Additionally, a variety of other cognitive tests that measured specific cognitive domains were employed.

Global cognition was examined in all systematic reviews, with MMSE and MoCA being the most used instruments. Positive effects of dance interventions on global cognition were consistently reported. However, Vega-Ávila et al. [41] found heterogeneous results.

Several cognitive domains were explored, including: Attention [8, 33,34,35,36, 39, 41] Executive functions [8, 33, 35,36,37,38, 40, 41] Language [8, 34,35,36, 41] Memory [8, 33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41]; Perceptual-motor function [35].

Memory was primarily assessed using the RBMT- Rivermead Behavioural Memory test [8, 34, 35, 38, 40, 41]. Short-term memory and immediate recall were assessed by DST – Digit Span Test [8, 33,34,35, 37, 39,40,41], and the WMS – Wechsler Memory Scale, to evaluate auditory, visual, and visual working memory [8, 33,34,35, 37, 40, 41]. The majority of the systematic reviews showed improvements on memory, except one [33] that showed little to no effects on this domain. However, the memory improvements were shown by different instruments and measures (e.g. delayed or immediate recall).

The TMT – Trail Making test A and B were listed in all systematic reviews to assess executive function, attention, psychomotor speed, and cognitive flexibility. Dance interventions showed improvements in attention and psychomotor speed [36, 39]. Enhancements in executive functions and cognitive flexibility were also reported [39, 40].

Most systematic reviews assessed quality of life (QoL), with the Short Form Survey Instrument (SF-36) and 12-Item Short Form Survey (SF-12) [8, 34, 36]. Mixed results were observed for overall QoL, with Huang et al.[8] reporting both positive and non-significant outcomes, while Wu et al. [34] and Liu et al.[36] reported non-significant results. However, subgroup analysis using the SF-12 revealed a positive effect of dance on QoL [34, 36].

Four systematic reviews analyzed mental health, specifically depression and anxiety. Depression was assessed using the Geriatric Depression Scale (GDS) [8, 34, 36, 37] and the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS) – depression subscale [8, 34, 36]. Dance demonstrated a positive impact, reducing depression levels in three systematic reviews [8, 36, 38], while one systematic review reported weak and non-significant effects [34]. Anxiety was assessed using the HADS – anxiety subscale [8, 36]. Two systematic reviews suggested potential effects of dance interventions in reducing anxiety [8, 36] while one study reported mixed findings [36]. Physical outcomes were also evaluated in some systematic reviews, focusing on balance and functional mobility.

Balance was measured using the Berg Balance Scale (BBS) in four systematic reviews [34, 36, 37, 39]. Functional mobility was assessed by the Timed Up and Go test (TUG) in two systematic reviews [34, 36]. The results for physical outcomes were controversial. While some systematic reviews reported improvements in balance and functional mobility [37, 39], others found non-significant or mixed effects [34, 36].

All the outcomes and instruments used in the included studies are available in the supplementary file S6.

Certainty of evidence

Overall, the certainty of evidence in the global cognition and cognitive domains ranged from low to very low, with all systematic reviews presenting very low evidence for global cognition evaluated by MMSE and MoCA. One systematic review [40] provided low-quality evidence for global cognition assessed using the Alzheimer’s Disease Assessment Scale-Cognitive Subscale (ADAS-cog).

Regarding executive function, 10% of the systematic reviews showed high certainty of evidence [38], 40% low certainty [8, 34, 36, 39], and 50% very low certainty[33, 35, 37, 40, 41].

Other cognitive domains demonstrated moderate evidence on memory [8, 33, 40], complex attention [33], verbal fluency [40] and language [34].

Heterogeneity among studies was identified as the primary source of bias. Most systematic reviews exhibited a risk of bias, except one [38] which showed no significant bias.

The certainty of evidence assessment is available in the supplementary file S7.

Meta-analyses

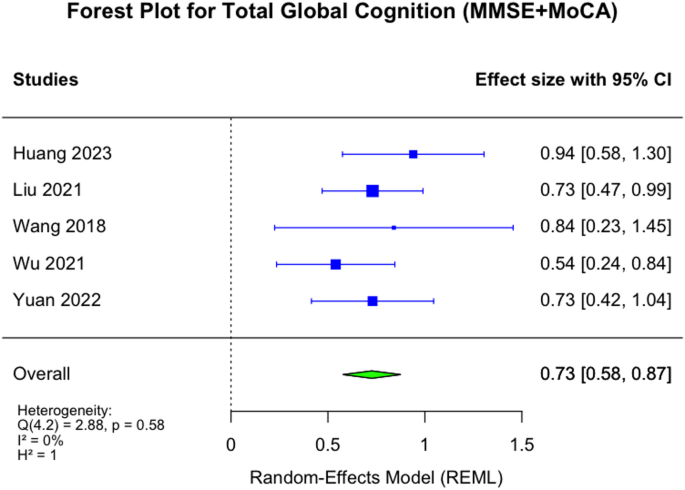

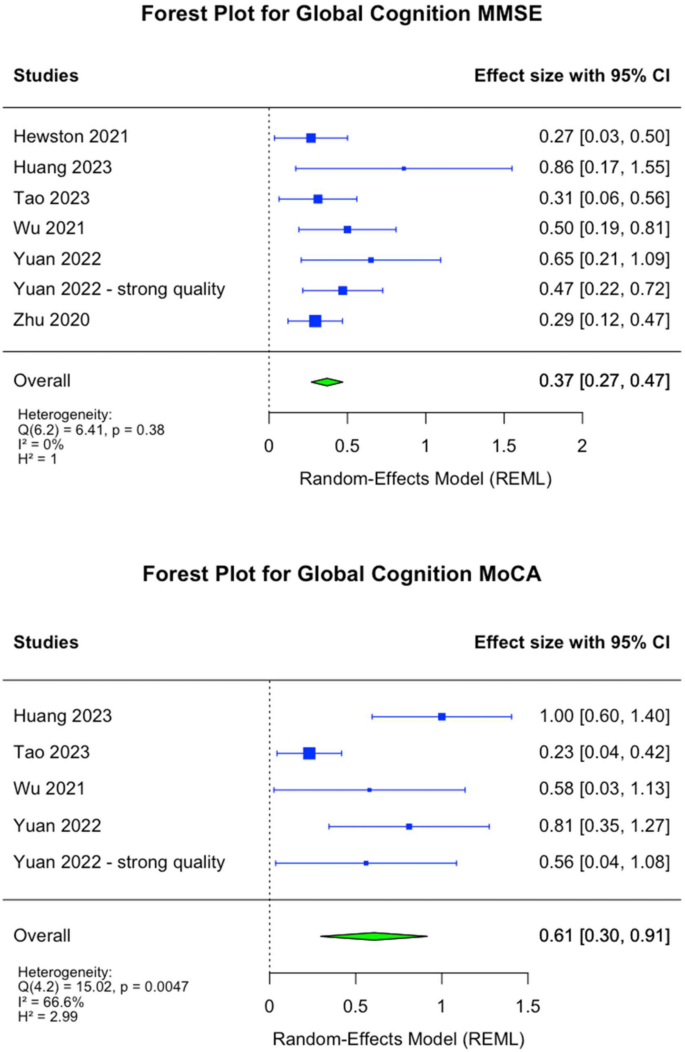

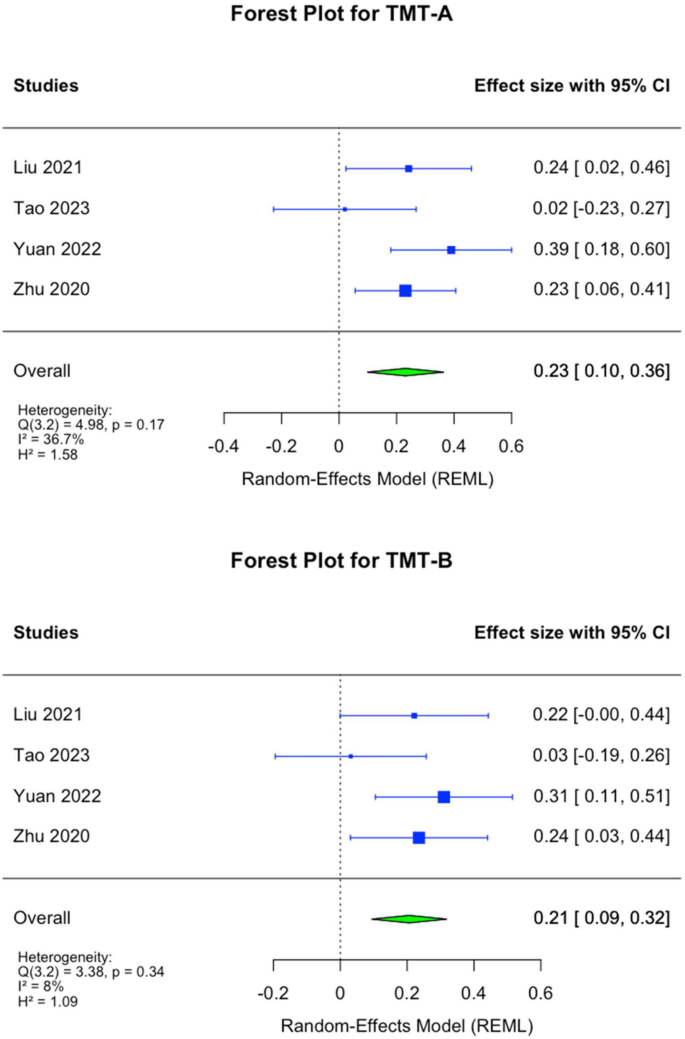

Effect sizes representing the standardized mean difference (SMD) between interventions are presented in Figs. 3, 4 and 5 with 95% confidence intervals and an overall pooled estimates. Meta-analyses showed significant effects of dance intervention on global cognition. The MoCA scores increased (SMD = 0.61, 95% CI: 0.30 to 0.91, p < 0,001) with high heterogeneity (I² = 66.6%); MMSE scores increased (SMD = 0.37, 95% CI: 0.27 to 0.47, p < 0.001) with low heterogeneity (I² = 0%); and, combined MMSE and MoCA scores increased (SMD = 0.73, 95% CI: 0.58 to 0.87, p < 0.001) with low heterogeneity (I² = 0%). Significant effects were also observed on cognitive domains. The TMT-A scores improved (SMD = 0.23, 95% CI: 0.10 to 0.36, p < 0,01) with moderate heterogeneity (I² = 36.7%); and, TMT-B scores improved (SMD = 0.21, 95% CI: 0.09 to 0.32, p < 0,01) with low heterogeneity (I² = 8%). However, the observed heterogeneity should be interpreted with caution, as it may be influenced by the small amount of variability between studies and the small number of systematic reviews included in each meta-analyses [42].

Methodological quality

Three systematic reviews were classified as critically-low [8, 33, 40] while seven were rated as low [34,35,36,37,38,39, 41]. The most critical methodological weaknesses identified were the absence of a comprehensive literature search strategy and the failure to provide a list of excluded studies with accompanying justifications for their exclusion. The methodological quality of the included systematic reviews is available in the supplementary file S8.

The included systematic reviews demonstrated substantial overlap, indicating that several reviews included the same primary studies. Substantial overlap was observed between Huang et al. [8] [ and Yuan et al. [39] , as well as, between Liu et al. [36] and Tao et al. [37] , with each pair sharing eight overlapping studies. Of the 29 individual studies included across the 10 systematic reviews and meta-analyses assessed, five were repeatedly cited in most reviews: Lazarou et al.[43] was included in all systematic reviews (10); Doi et al. [44] was included in 8 out of 10; and Bisbe et al. [12], Qi et al. [45] and Zhu et al. [21] were each included in 6 out of 10 systematic reviews. The detailed overlap of included studies across systematic reviews and meta-analyses is presented in supplementary file S9.